|

|

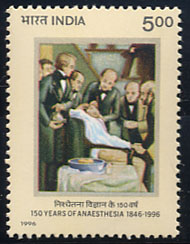

| Emission : 1996 | N° Y. & T. : n° 1297 |

|

|

||

Thème :

150e anniversaire de l'anesthésie 1846-1996

Commentaires :

Le terme d’anesthésie exprime la perte des sensations.

C’est

William T. G. Morton qui, en 1846, fit la première démonstration

publique de l’emploi de l’éther pour produire un tel état

d’insensibilité pendant une intervention chirurgicale. Mais, dès

1799, Humphrey Davy décrivait les propriétés anesthésiques

du protoxyde d’azote et Horace Wells, en 1844, s’administra à lui-même

du protoxyde d’azote pour une extraction dentaire.

L'anesthésie

à l'éther a été introduite en France par Malgaigne

en 1847. Le chloroforme l'a été vere le même date.

Le protoxyde d'azote a été introduit à Paris par

Thomas Evans (1860) et Préterre.

William

Green Morton.(1819-1868).

Dentiste installé à Boston, il utilise aussi le protoxyde

d'azote, mais d'autre part, il avait également remarqué

les effets anesthésiants de l'éther, appliqué localement

sur une dent douloureuse.

Le 30 septembre 1846,il effectue avec succès et sans douleur, une

extraction dentaire sous éther.

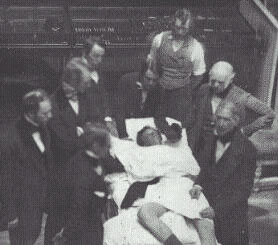

Le 16 octobre 1846, contrairement à son homologue Wells, Morton

pratique une anesthésie générale par inhalation d'éther

sulfurique pour un patient du chirugien Warren, le jeune Edward Gilbert

Abbott. Celui-ci souffre d'une tumeur du cou. L'intervention se déroule

parfaitement, le patient n'a rien senti. C'est un succès sans précédent.

Encore la querelle de la priorité.

Alors qu'en France comme en Angleterre et bientôt dans toute l'Europe

continentale, les éthérisations se multiplient, Jackson

et Morton et bientôt Wells s'entredéchirent pour la reconnaissance

de la priorité de l'invention et des bénéfices qui

s'y rattachent. Ils prendront à témoin les Français.

Le pli cacheté de Jackson ouvert à l'Académie des

Sciences le 18 janvier, à défaut d'avoir initié l'anesthésie

chirurgicale en France, a produit son effet. Elie de Beaumont souligne

la renommée de Jackson et insiste sur << ses titres scientifiques

qui recommandent sa découverte à l'attention de l'Académie

>> 32. Pour les savants français l'anesthésie est

donc due à Jackson. Pourtant Horace Wells écrit en février

à l'Académie de Médecine 33 et à l'Académie

des Sciences 34, pour revendiquer sa priorité : << La découverte

que j'ai faite, ne consiste pas uniquement dans l'emploi de l'inhalation

de l'éther, mais dans le principe même qui établit

la possibilité de la production de l'insensibilité, par

l'usage de divers agents, tels que gaz protoxyde d'azote, vapeurs d'éther

sulfurique, etc. >>

Elie de Beaumont soutient que << le véritable bienfaiteur de l'humanité >> est bien Jackson, << celui qui le premier a engagé un dentiste à essayer d'extraire une dent à une personne placée sous l'influence de l'état particulier que produit l'inhalation de la vapeur d'éther. >>35. Wells devra se contenter d'une statue édifiée post-mortem sur la place des Etats-Unis à Paris.

Monument élevé à la mémoire de Horace Wells en 1910, place des Etats-Unis à Paris.

AU DENTISTE AMERICAIN

HORACE WELLS

NOVATEUR DE

L'ANESTHESIE CHIRURGICALE

1844-1848

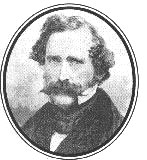

Portrait de Horace WELLS (1815 - 1848)

Inventeur de l'anesthésie

peint par Charles Noel Flagg en 1899

Musée à Hartford(CT)

Morton's first successful public demonstration of ether anaesthesia for a surgical operation, performed on October 16, 1846 in Boston/Massachusetts, had far-reaching consequences. The first effect was the surprisingly fast propagation of the new way of preventing pain to nearly all parts of the globe. Anaesthesia made it possible to perform operations previously considered impossible under conditions now acceptable for the patient. From the beginning, recurring side effects and complications made it necessary to collect and report these and to look for improvements or alternatives. This led to the development of local and regional pain relief procedures. Much later, the special field of anaesthesiology emerged. Today, 150 years after Morton's pioneer work, anaesthesiology comprises not only pain relief for operative procedures but also responsibilities in Emergency and Critical Care Medicine and in the treatment of patients with chronic pain. Accordingly, without the least disparagement of daily interdisciplinary cooperation, one can wholeheartedly support Mayrhofer's view that the "Century of Surgeons" has given way to the "Century of Anaesthesiologists".

As a young man, William Morton learned about the torments of surgery. He underwent an operation without anaesthesia in Cincinnati. Fortunately, he survived.

Morton was born in 1819 in Charlton, a village in Worcester County, Massachusetts. He had a common school education at Northfield and Leicester Academies. Morton tried his hand variously as a clerk, printer and a salesman in local Boston business houses. But he didn't find the work either satisfying or lucrative.

In 1840, Morton enrolled at the world's first dental school, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. He left without graduating. Instead, in 1842-3 Morton became a pupil and then business partner of Hartford dentist Horace Wells. The partnership wasn't a great success. It was dissolved after six months.

Shifting track again, in 1844 Morton became a student at Harvard Medical School. He signed up partly to increase his medical knowledge, but partly it seems to impress the woman he loved and later married, Rebecca Needham. Again, Morton never completed his degree. To improve his understanding of chemistry, he attended the lectures of Professor Charles Jackson, from whom he first learned of the properties of ether. During 1844, Jackson demonstrated before his chemistry classes that the inhalation of sulphuric ether causes loss of consciousness. In the light of Jackson's later claim to be the inventor of etherization, it is puzzling why he did not ask one of his surgical colleagues at Harvard to apply this knowledge and practise painless surgery. The pre-history of anaesthesia is a long chapter of missed opportunities.

Morton continued his dental practice as a means to finance his medical studies. Over a decade before, he had introduced a new kind of solder by which false teeth could be fastened on to gold plates. It was clearly desirable to find a good method of extracting the roots of old and diseased teeth with the minimum of pain. Morton initially experimented with opium, stimulants and Mesmerism. Opium relieves pain; dopaminergic stimulants can indeed act as analgesics too; and Mesmerism can sometimes work with extremely suggestible patients and a charismatic doctor. Yet none of these options proved satisfactory.

Fortunately, inspiration was imminent. Morton was present in the surgical amphitheatre in Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) when his former business partner, Horace Wells, failed to convince a scornful young audience that nitrous oxide offered a route to painfree surgery. Morton consulted his erstwhile tutor Professor Jackson about the possibility of using a stronger agent. Neither man could later agree on precisely what Morton asked, nor how Jackson responded; but most scholars believe that Jackson advised Morton to use ether. After conducting various experiments on himself and other animals, Morton successfully conducted a dental extraction in his office on Boston merchant Eben Frost. A favourable journalistic account of this exploit in the local Boston press caught the eye of junior surgeon Henry Bigelow. Bigelow arranged with MGH head surgeon John Collins Warren to stage a public performance of the revolutionary procedure.

At the appointed hour, Morton did not appear. So Dr Warren prepared to start operating on his terrified patient in the time-honoured manner. Then Morton hurried into the amphitheatre. He was late because he had been fiddling with his "Letheon" inhaler, the newly-designed ether-delivery apparatus he was seeking to patent. His tardiness increased the scepticism of the audience of medical students and surgeons. Much to their astonishment, however, both the anaesthetic and the operation passed off peacefully. Until the anaesthetic era, surgery was typically an exceedingly noisy affair, punctuated by blood-curdling screams and piteous moaning from a writhing patient. But this operation was conducted in rapt silence. 52 year-old printer Edward Gilbert Abbott (1825-55) inhaled from the Letheon, passed out, lay insensible throughout Warren's excision of his vascular tumour; and then revived unharmed. Bigelow wrote up Morton's triumph in his paper Insensibility during surgical operations produced by inhalation. The news soon echoed round the globe, mid-19th century communication structures permitting.

Avaricious and unscrupulous, Morton was not quite the monster of depravity he has been painted by revisionist historians. He offered free rights to his innovation to all charitable institutions throughout the country, and undoubtedly he was ardently in favour of the abolition of surgical pain, albeit with profit to himself. Morton administered ether anaesthesia to thousands of stricken soldiers in the American Civil War.

Yet Morton's later years were rarely happy. He petitioned US Congress three times for recognition of his priority, and rights to the profits derived therefrom. He even managed to secure an a interview with the fourteenth President of the USA (1853-57), Franklin Pierce, to press his case. Morton was unsuccessful. His nemesis, Professor Jackson, still had influential friends. Other candidates for glory, notably Wells and Dr Crawford Williamson Long, also surfaced to muddy the waters. Litigation consumed Morton's energies and drained his limited funds. Away from controversy, he spent time in agricultural pursuits in Massachusetts, where he raised and imported fine cattle. But the failure of the world adequately to recognise and reward his unique contribution to human well-being rankled deeply as long as he lived.

At the age of 48, Morton died suddenly of “congestion of the brain”, probably a cerebral haemorrhage. Deeply in debt, he had travelled to New York City in the middle of a deadly summer heatwave. Morton had been outraged to read an article in the Atlantic Monthly that credited the invention of etherization to Professor Jackson. Jackson outlived his student, but died in an asylum, insane.

Liens :

http://www.franc-maconnerie.org/default.html

http://www.char-fr.net/docs/textes/h_wells/

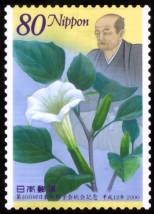

SEISHU HANAOKA (1760 – 1835)

voir lien

Pionnier de l’anesthésie et de la chirurgie japonaise

Incontestablement Hanaoka fut un visionnaire et un génie dans ses conceptions de la médecine. Il mérite d'être connu dans le monde occidental autant par l'impulsion qu'il a donnée à la chirurgie que par son souci de développer une analgésie lui permettant de réaliser des interventions complexes qui ne seront effectuées que plus tard en occident. Il est le père d'une anesthésie qui n'eut certes pas de suite mais qui était en avance sur tout ce qui se faisait à l'époque. Il est curieux de constater que l'opium connu des asiatiques n'incita pas tant les médecins chinois que japonais à l'utiliser.

timbre : 100th Congress Japan Surgical Society (11 avril 2000)

| Taille : | Dessinateur : | ||

| Dentelure : | 13 x 13 1/2 | Couleur : | multicolore |

| Valeur(s) : | 5 r(oupies) | N° Scott : | |

| Autre pays : | Transkei |

Lien :